Author: pixel2coding

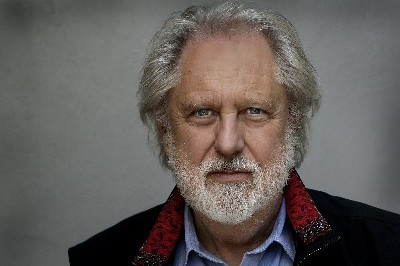

Atticus Education, The University of Sunderland, North East Screen and Pinewood Group are delighted to present a special evening in conversation with Lord David Puttnam, one of the legends of British Cinema.

The multi-award-winning film producer will reveal the stories behind some of his greatest movies including Chariots of Fire, The Mission, The Killing Fields, Midnight Express and Local Hero at The Fire Station in Sunderland on Tuesday 11th October.

Using excerpts from these films, for which he has received numerous Academy Awards, BAFTA’s and the Palme D’Or in Cannes, he describes how his career took him from 30 years in the Hollywood- dominated film industry to 24 years in Westminster, where he shaped policy in the areas of Media Ownership, Climate Change, Education, Disinformation and Online Safety.

The event will take place in The Fire Station Auditorium, Sunderland’s brand new and state of the art performance venue set in the heart of the city’s cultural quarter. Tickets will cost £5 with all proceeds going to UNICEF’s Ukraine Children’s Appeal.

Of the event, David Puttnam said, “I’m very much looking forward to being back in Sunderland, not only to meet the University’s talented new Puttnam Scholars in-person, but also to spend an evening revisiting these feature films and some of the tales and anecdotes from the past 50 years. Whilst I hope the evening will be enjoyable for the audience, I am overjoyed that we are also able to together support UNICEF and its critical appeal for the children of Ukraine.”

Tickets are now available via The Fire Station website: www.thefirestation.org.uk. The event will begin at 7.30pm.

Further information:Amy Castle

Head of Communications, Atticus Education amy@davidputtnam.com

07764 355 045

About Atticus Education

Atticus Education is an online education company created by film producer and educationalist, Lord Puttnam. Atticus delivers live interactive seminars to educational institutions around the world, providing high-quality resources to support learning using advance digital distribution systems. Atticus provides content relating to different aspects of the creative industries. David Puttnam is the chair of Atticus Education. He spent thirty years as an independent producer of award-winning films including The Mission, The Killing Fields, Local Hero, Chariots of Fire, Midnight Express, Bugsy Malone and Memphis Belle. His films have won ten Oscars, 31 BAFTAs and the Palme D’Or at Cannes. From 1994 to 2004 he was Vice President and Chair of Trustees at the British

Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) and was awarded a BAFTA Fellowship in 2006. He retired from film production in 1998 to focus his work on public policy as it relates to education, the environment, and the creative and communications industries. He was awarded a CBE in 1982, a knighthood in 1995 and was appointed to the House of Lords in 1997 and retired in 2021. In France he was made a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters in 1985, becoming an Officer in 1992, and a Commander in 2006. He is the recipient of over 50 Honorary Degrees, Diplomas and Fellowships from the UK and overseas. https://www.davidputtnam.com/masterclass-seminars @DPuttnam

Puttnam Scholars Scheme returns for third Summer Programme

08 June, 2022

Atticus Education, Fís Éireann/Screen Ireland, Northern Ireland Screen and Future Screens NI are delighted to announce the return of the Puttnam Scholars scheme for the third year running.

The pioneering cross-border initiative provides eight individuals four Northern Ireland residents and four from the Republic of Ireland) the opportunity to attend six two-hour online masterclasses with Oscar-winning producer Lord David Puttnam (Midnight Express, Chariots of Fire, The Mission, The Killing Fields).

The participants receive a special Scholarship from Atticus Education for their future career development. The scholarship bursaries are supported by Accenture in Ireland. Screen Ireland are working closely with four Irish universities to select four Puttnam Scholars from the Republic of Ireland, while Future Screens announced the recruitment process in Northern Ireland earlier this month. The Puttnam Scholars’ application form for Northern Ireland applicants is available on the Future Screens NI website.

Lord Puttnam said: “We created this initiative in 2020 and its already developed as a unique opportunity in the development of an exciting new generation of talent. Cinema is a vital medium for developing understanding, all the more so as we tackle serious global issues and increasingly turbulent times. This successful collaboration, between Atticus Education, Screen Ireland, Northern Ireland Screen, Future Screens NI, and supported by Accenture, has already enabled two cohorts to advance their futures in the screen industries; I’m greatly looking forward to meeting the next eight participants.”

Applying to the scheme as up-and-coming writers, directors, or producers, the chosen Puttnam Scholars will have either made their first feature or television drama or will be in the process of developing their first feature or television drama.

A Puttnam Scholar, Isabella Dijalil-Devine, said of her experience in 2021’s cohort that “the programme was inspiring, informative, and fun. Lord David Puttnam and his guests shared their advice and experience generously, not just about filmmaking but also about the industry as a whole. I felt very motivated and encouraged to take steps in my career, and I am very grateful to have had the opportunity to take part.

Over the course of the sessions, Lord Puttnam will explore the following themes: The Power of Identity; The Evolution of Creativity; Fact or Fiction; Builders and Brokers; Music and Meaning; and Interpreting the Future.

Alastair Blair, Country Managing Director, Accenture Ireland said, “We’re delighted to, once again, support the Puttnam Scholars Scheme. Ireland’s screen and creative industries are thriving, making a significant contribution to the economy each year. Programmes like these, which focus on the ongoing development of Irish talent and encourage the next generation of filmmakers to build their careers, are vital in ensuring that Ireland is a creative capital, now and into the future.”

The masterclasses will be online and fully interactive with special guests and content appearing across the course. The sessions are designed to enhance participants’ understanding of the creative process and the cultural context within which the screen industries operate.

|

Amy Castle Communications Atticus Education |

Brian Oh Marketing & Communications Coordinator Screen Ireland |

Deirdre Mac Fadyen Business Support Future Screens NI de.macfadyen@ulster.ac.uk +44 7716 700068 |

|

|

|

|

About Atticus Education

Atticus Education is an online education company created by film producer and educationalist, Lord Puttnam. Atticus delivers live interactive seminars to educational institutions around the world, providing high-quality resources to support learning using advance digital distribution systems. Atticus provides content relating to different aspects of the creative industries. David Puttnam is the chair of Atticus Education. He spent thirty years as an independent producer of award-winning films including The Mission, The Killing Fields, Local Hero, Chariots of Fire, Midnight Express, Bugsy Malone and Memphis Belle. His films have won ten Oscars, 31 BAFTAs and the Palme D’Or at Cannes. From 1994 to 2004 he was Vice President and Chair of Trustees at the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) and was awarded a BAFTA Fellowship in 2006. He retired from film production in 1998 to focus his work on public policy as it relates to education, the environment, and the creative and communications industries. He was awarded a CBE in 1982, a knighthood in 1995 and was appointed to the House of Lords in 1997 and retired in 2021. In France he was made a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters in 1985, becoming an Officer in 1992, and a Commander in 2006. He is the recipient of over 50 Honorary Degrees, Diplomas and Fellowships from the UK and overseas. https://www.davidputtnam.com/masterclass-seminars @DPuttnam

eQuinoxe Europe announces a new Creative Producing masterclass in collaboration with Atticus Education. There will be six classes overall, with five online and one in-person. Further details on the application process will be announced on the eQuioxe Europe website later this month: News eQuinoxe Europe (equinoxe-europe.org).

Shirley Williams Memorial Lecture. October 15th 2021 19:00

POWER AND FEAR – THE TWO TYRANNIES

Before I begin, I’d like to offer my sincere condolences to the whole of the Amess family – what happened today is not just a tragedy for them but for all of us who believe that democracy must operate free of fear at a constituency level. As with Jo Cox five years ago, our MPs, whilst protected within Westminster, remain vulnerable when doing the vital public facing aspect of their role.

It’s for these reasons I want to talk this evening about the multiple dangers faced by Democracy – for me today’s shocking events simply strengthen the case for continual vigilance.

Probably the most overused phrase at a moment like this is: “what an honour it is to be speaking at an event which memorialises – whoever”; but the truth of that sentiment couldn’t be more sincerely felt this evening, nor carry with it more responsibility.

Shirley was an admired friend and major influence for almost fifty years – there are not half a dozen people in public life who have more accurately reflected the expectations I’ve hoped for myself.

We shared the privilege of having parents who had risked a great deal and gave up chunks of their life to make the world a better, safer place.

In her phrase they had “a commitment to the idea and the ideal of public life”.

In her own life she left us with an almost impossible debt to repay – but this evening I’m going to give it a shot.

I’ve done a fair bit of reading and revision in preparing for this lecture and, as most members of the House of Lords will acknowledge, it’s a wonderful sense of relief not to constantly have to check a word count to stay within the five, four or even three-minute speaking times that have become commonplace.

How it’s possible to make a persuasive argument within those restrictions is totally beyond me – I frequently reflect upon the 272 words in the Gettysburg address – and then remember that Lincoln’s speech was essentially an ‘assertion’ not an argument – although history has judged it as both.

This issue of ’assertions’ is one I’ll be returning to; but I can’t be the only member of the House of Lords who’s become increasingly frustrated by the fact that in Parliament, as elsewhere, we no longer engage in serious ‘debate’ – we simply trade assertions.

‘Debate’ as I have always understood it, is ‘persuasion’ based on competing interpretations of evidence; and the ability to form a compelling argument and, where necessary, seek compromise.

Sadly, that’s been substituted by a ‘dialogue of the deaf, typified by the Government’s refusal to answer serious questions, or offer any well-thought-through arguments in defence of seemingly immutable positions.

Their view appears to be ‘we are the Government – take it or leave it!’

To say that I find it disheartening would be an understatement.

Over the course of the next thirty minutes, at times using Shirley’s own words, I’ll argue that not only does the world in general find itself in a bad place, but I’ll try to set out some of the reasons we find ourselves careening down a path to self-inflicted disaster or, in the case of the UK, irrelevance.

I was tempted to use a more ambiguous word than ‘disaster’, but that would only be adding to the pile of misinformation in which we’re already drowning.

A large portion of my life has been spent as a cinematic storyteller.

But I’d suggest that all thirty of the films I made for film and television tried, with mixed success, to offer something beyond a straightforward narrative – something for the audience to discuss and perhaps even argue about long after they’d left the cinema.

So was there a particular insight I kept trying to get across – and if so, what might have been its gestation?

Early on in my career I could only draw from a couple of dozen uneventful, but easily illustrated years growing up in the North London suburbs.

I was the quintessential beneficiary of the policies of the post-war Labour Government – in health, in social security and, as one who squeezed over the hurdle of the eleven-plus – even in education.

That “revolution by consent” Shirley used to refer to.

By my late twenties I’d been responsible for three or four films set against the background of those early experiences, the success of which had given me some limited credibility as a producer.

So much so that in 1971, together with my partner and friend, Sandy Lieberson, I had the audacity to bid for the rights to a book which had become a huge international best seller.

That book was ‘Inside the Third Reich’ by Albert Speer.

We were rank outsiders in pursuit of these rights, but the publisher generously agreed that we might at least travel to Heidelberg and make our case in person.

Albert Speer, Hitler’s former Architect and Armaments Minister had walked out of Spandau prison five years earlier, having served twenty years for war crimes – he patiently listened for several hours as we took him through our reasons for wanting to make the film and, to our amazement, he agreed that if a movie was to be made, it should be produced by and for a younger generation.

That was the start of an adventure which took us and our screenwriter Andrew Birkin on numerous occasions back and forth to Heidelberg.

It was during those conversations with Speer that I came to understand what we now call ‘the fascist play book’ – the way democracy can be corrupted and overturned by a few malevolent but persuasive politicians, those who are prepared to exploit divisions in society with simple populist messages.

He explained the extent to which we were all vulnerable, and the importance of developing the form of ‘moral vigilance’ required to recognise nascent evil for what it is.

Having joined the National Socialist Party in 1931 with a view to furthering his career as an Architect, what should have been the moment of truth came seven years later.

Driving to his office on November 1938 he passed the smouldering ruins of Berlin’s synagogues, the result of the orchestrated riots of the previous night – ‘Kristallnacht’.

As he puts it in his book, “most of all I was offended by the smashed panes of shop windows which offended my sense of middle-class order” – he goes on: “what I didn’t see was that more was being smashed than glass, that on that night Hitler (actually Germany) had taken a step that irrevocably sealed the fate of his country.”

He concludes: “did I sense that this outbreak of hoodlumism was changing my own moral substance? I do not know.”

A more politically astute man would have realised that Rubicon had been crossed five years earlier, in the aftermath of the Reichstag Fire and the subsequent Enabling Decree, which effectively disbanded Parliament and handed absolute power to Hitler.

The full title of the Act was ‘The Decree for the Protection of the People and the State’.

It’s an interesting word ‘enabling’, it sounds fairly harmless – as in ‘enabling’ a child or an elderly person to safely cross a road.

How often do powers accrue to Parliament through a piece of legislation whose intent is the precise opposite of its title?

Take for example the present Government’s plans to revise the Data Protection regime, their consultation allows for the impression that they’re simply ‘freeing us up from bureaucracy’, when by far the most likely outcome is the privatisation, exploitation and sale of our personal data.

It might be a good idea to take a long hard look at what else is coming down the track.

An ‘Elections Bill’ that, contrary to the advice of the Committee for Standards in Public Life, is set on undermining our long established independent ‘Electoral Commission’; a Bill to reform Judicial Review whose principal aim is to reduce the role of the Judiciary; a Police Bill that weakens the right to legal protest; along with a plan to ‘widen the scope of the Official Secrets Act’ with no commitment to add a public interest defence for journalists – even an Education Bill that seeks to reduce traditional academic freedoms in the area of Teacher Training! All of this accompanied by continued mutterings about ‘unelected judges’ in Strasbourg, and ‘reforming’ the UK’s implementation of the European Human Rights Act, potentially forcing us out of the Council of Europe.

And with every passing month there are more – each of them setting out to chip away at and undermine much of what defines an active liberal democracy: those institutions that might act as checks and balances on a populist government that’s trampling on long held rights and conventions, with the sole purpose of tightening its own grip on power.

Which is why a free and fearless media is essential to democracy.

So when the Prime Minister actively – and repeatedly – intervenes to manipulate an ideological ally into the Chairmanship of Ofcom, every alarm bell should start to ring signalling the absolute nonsense that’s being made of the regulator’s independence.

It’s worth pausing here to remind ourselves that Ofcom’s primary duty, as amended in the Commons, and set out in her speech of Monday 4th July 2003 by my greatly missed friend the then Secretary of State, Tessa Jowell, is as follows:

“Ofcom shall have a primary duty to citizens and consumers whose interests shall be equal. Furthermore, when the duty to the consumer and the duty to the citizen come into conflict, there will be transparency and accountability.

Ofcom will publish a reasoned statement as soon as possible after a decision setting out how the duties came into conflict, how Ofcom resolved that conflict, and the reasons behind its decision.”

Importantly, she concluded:

“The communications industry is not like any other industry: it is central to the health of our society and the health of our democracy.”

That is why being Chair of Ofcom is unlike almost any other position of trust, and cannot be safely placed in the hands of anyone with a discordantly ideological turn of mind.

It will be similarly fascinating to see how the newly installed Secretary of State chooses to interpret her brief to ‘protect a public service ethic that is distinctively British’!

No government in the world has inherited a more comprehensively tested ecosystem of public service broadcasting. That’s why our formats, ideas, talent, humour and values so effortlessly, and successfully travel around the world. By chipping away at an area of public service the government so clearly loathes, they are in fact undermining precisely that ‘distinctiveness’ they claim to treasure!

When you add the commercially illiterate and ideologically vindictive proposal to ‘purify by privatisation’ Channel Four, you begin to see how easily our carefully constructed public broadcast system can be smashed to pieces.

Mention of the DCMS brings me back to that ‘Digital Democracy’ report I mentioned at the outset, and in particular the Government’s draft Online Safety Bill.

In my view, the Bill in its present form does not go anything like far enough in addressing the issue of personal responsibility, or redress for the profound societal harm caused by tech-enabled misinformation.

What the principal shareholders of the social media companies know is that the type of adjustments that could be made to their algorithms are likely to adversely impact their ‘reach’, and therefore their revenues.

The founders of these companies, even the best of them, cannot find it in themselves to confront their shareholders with the consequent reduction in ‘market value’.

So, despite the fact that they know exactly what they could do to tweak their algorithms, and make them safer, they concoct the same stream of misinformation they facilitate on a daily basis, to protect what is already a dysfunctional business model.

This is capitalism quite literally eating its young.

If you want further evidence, and have one minute 40 seconds to spare, go on to YouTube.

There you can search for and easily find the evidence given before the Congress in 1994 by the US tobacco barons – swearing on oath that nicotine was not harmful, and there was no relationship between nicotine and poisoning. Three years later that issue was settled with a fine-payment of over $200 billion, but no acknowledgement of personal responsibility.

To me, we are heading down exactly the same road with the social media companies.

At the time of that congressional hearing every one of those men had, for 15 years, received all the evidence they could possibly need to know that cigarettes were in effect ‘nicotine delivery tubes’, responsible for the death of thousands of people a year.

As a self-confessed nerd, I also spent a good number of years looking at Road Traffic Acts, and the way the Automobile Industry ignored the issue of safety for almost half a century.

We have to get a whole lot smarter in looking at the history of these failures – to learn from our mistakes and challenge our seeming complacency. Corporate responsibility and it’s imposition has been evaded for far too long and, even when it is imposed its almost always based on the concept of ‘fines’.

Fines have never been enough.

If we are serious about grabbing the attention of Boards towards their ‘duty of care’ then we have to create far clearer lines of accountability.

I’ve sat on numerous Boards over the past fifty years, and the one certain way to make Directors and senior managers to sit up and take notice is when the ‘risk register’ flags up the issue of personal responsibility.

There is something deeply flawed in the response of the global tech monoliths to criticism, their instinct is to believe that they can always ride it out.

They may of course be right, because the truth is only Parliament can bring them under control.

It’s in Parliament that the buck stops; but on present evidence it’s also where much of the will stops.

MPs are busy people and tend to react to events rather than get ahead of them, but I’d suggest they should sit up and take particular notice where online harms to young people are concerned.

Unless a tougher regulatory regime is imposed on the social media companies than presently appears on the face of the draft Bill then I’ll bet a pound to a penny that, over the course of the next Parliament, literally dozens of MPs will find themselves dealing with a ‘Molly Russell’ case in their own constituencies;

and God help them if they are unable to explain to parents why, when they had the opportunity to strengthen the law and the penalties it carried, they chose not to.

I don’t think there is further room for cosy compromises; ‘big tech’ can no longer be seen as too big to prosecute, any more than can ‘big energy’ or ‘big finance’. All have to accept their clear ‘duty of care’.

Much of this was confirmed by Frances Haugen’s recent and remarkable testimony to Congress in respect of Facebook.

Indeed, were I ever to have made a film about a whistle-blower I’d hope to cast someone who came across with the poise and integrity of Ms. Haugen!

A read-across from Albert Speer would suggest that her testimony may well be Facebook’s ‘Faustian moment’. This is surely the point at which any right-thinking employee should say to themselves “enough is enough – I need to stop defending the indefensible and reset my moral compass”.

In raising the issue of harms to young people it seems worth stressing that, as a nation, we’ve been hopelessly lax in developing initiatives to empower vastly improved digital literacy among children and young people. There is an obvious need to invest in projects that will encourage them to think far more critically about the content they consume, most especially online.

Unacceptable delays have resulted from the buck being passed from department to department, all the time ignoring the fact that Public Service Media has a critical role to play.

We’ve already witnessed some really useful initiatives from the PSBs – you only have to look at the value children and their parents have extracted from the BBC’s educational output during the pandemic, and the range of resources that are now available via BBC Teach, to see what could be possible.

Taking a step back for a moment, Dick Newby, in his generous introduction, mentioned my decision to retire from the House of Lords later this month. That was not a decision arrived at lightly and maybe it deserves a little explanation, possibly even some additional justification.

As I’ve mentioned, for a little over a year, from the Spring of 2019 to the end of June 2020 I had the honour to Chair a Lords Select Committee on the impact of digital technology on our political processes.

I was fortunate to have around me a cross-party group, along with an exceptional support team, all of whom took our brief incredibly seriously.

Our final Report, with its forty-five evidence-based recommendations, was published in June of last year under the title ‘Digital Technology and the Resurrection of Trust’.

It was originally to be: ‘Digital Technology and the Restoration of Trust’, but the evidence – even then – was so damning that in the final draft I substituted the word ‘Resurrection’.

I believed and continue to believe that the ‘resurrection’ of our capacity to trust each other, and the systems through which we receive information – the same information on which we base many of the most important decisions of our lives – is fundamental to our survival as a coherent society.

I put it more simply in the Foreword to the Report – “without trust democracy as we know it will simply decline into irrelevance” – fifteen months later I’d add, ‘or worse’!

The only accurate way to describe the Government’s response to our Report is ‘lamentable’.

Little attempt was made to address the mountain of evidence, let alone build and improve upon the most thoughtful of our suggestions.

It came across as if written by a robot – and ‘the computer said no’!

That was, to put it mildly, disheartening – made worse because throughout the deeply unpleasant Brexit debates I’d been forced to watch Ministers malevolently twist, turn and posture in parading their prejudices, along with their, at times, downright ignorance.

Let me offer two examples which left me particularly gob smacked:

In discussions regarding the Republic of Ireland, and the complexity of finding sustainable post-Brexit solutions, I was staggered at the display of pig-ignorance towards the fundamentals of Irish history, let alone sensitivity towards the reality of cross-border relationships.

Had they really become so disconnected from the ghastly history of what we euphemistically call ‘the Troubles’?

As someone who lives just across the Ilen River from the site of what is probably the largest and most recent mass famine-grave on these islands, I may well be ultra-sensitive to these issues, but with a few notable exceptions, the level of empathy and understanding on display in both Houses was truly shocking.

To switch from the personal to the political; to hear from Government Ministers, with a straight face, that it was going to be relatively simple to negotiate a significant trade deal with the United States – all the while remaining blithely ignorant of the immense political sensitivities across the island of Ireland – was either astonishingly stupid or a downright lie.

To both these issues I tried to inject some contemporary and historical realism; to find all rational discussion utterly ignored.

If anything, this situation has only deteriorated, made significantly worse by the unprincipled and destructive outbursts of the recently ennobled Lord Frost in Lisbon on Tuesday evening, who seems to exist in a world entirely of his own imagining.

There is a short speech in the 1987 movie ‘Broadcast News’ that I’ve used a number of times when teaching my communication students.

At one point the character ‘Aaron’, played by Albert Brooks says:

“What do you think the devil will look like when he next comes around? Nobody’s going to be taken in if he starts flashing a long red pointy tail.

No, what he’ll do is just bit by bit lower standards where they’re important. Just coax along flash over substance …. just a tiny bit at a time!”

Maybe in our case he’ll substitute a long red bus for the long pointy tail; paint a massive lie on the side, and find a group of unprincipled acolytes to defend it!

Given all of this and more, at eighty I no longer find myself with sufficient patience to treat mendacious political inanity with the appearance of courtesy.

In 2005 and 2006 I chaired Hansard Commissions looking at ways in which the operations of the House of Lords might better reflect the, then new, century.

Fifteen years later I’m happy to say that at least some of the reforms we recommended have been implemented; a Chief Executive to work alongside the Clerk of the Parliaments; an accountable and publicly comprehensible set of reporting mechanisms, and a fit for purpose Communications Department.

A few years later I gave evidence to the Burns Review and recommended that fifteen years of active service and an eighty-year age limit would seem appropriate – I added that in exceptional cases those upper limits be increased to twenty and eighty five.

I added that my case certainly didn’t qualify as ‘exceptional’!

Having hit respectively twenty-four years and the age of eighty, it felt time to, as it were, ‘put my money where my mouth had been’.

Whilst I won’t miss the bi-weekly four-and-a-half-hour commute,

I’m definitely not leaving the Labour Party, and will greatly miss the collegiality of my colleagues, indeed I’ll miss the friendship and support the very many Peers I respect on all sides of the chamber.

I’ll certainly miss playing a part in the deliberations of my colleagues on the Environment and Climate Change Committee, and I’ll be equally sorry not to engage with the cut and thrust that will undoubtedly accompany the contentious passage of the Online Safety Bill; but as I suggested at the conclusion of what turned out to be my final speech in the House:

“With all the force I can muster I beg those many decent Conservative Peers and Members of Another House, those with a concern for the principles of parliamentary democracy, to do what sooner or later they will have to do: muster the courage to say to the Prime Minister and his seemingly supine cabinet ‘in God’s name go’.

Go before you destroy the last sliver of self-respect that our country can call its own”.

I’m only too aware of the irony that, having spent almost sixty years seeking cross party support for those things I most believed in, I’m left looking to the Conservative party to offer a lifeline to the concept of an informed plural democracy.

Since joining the House of Lords all those years ago, and entirely contrary to popular myth, I’ve always seen the Chamber as likely to be the ‘last man standing’ when the fight to sustain a citizen-led democracy reaches its end game.

Twenty-four years ago, when I went through the ritual of establishing my ‘désignation’ at the College of Heralds I was informed that the name Puttnam (with a variety of spellings) had a Norman antecedence, a crest, and even a motto.

That motto was ‘To Serve is to Live’ – more than ever in leaving the House as a working Peer I realise what an incredible privilege it’s been to be allowed to serve the country in a variety of areas – through incredibly happy years at the Department of Education, across work with numerous Committees, and most recently through the misunderstood and much maligned role of a Trade and Cultural Envoy to, in my case, South East Asia.

In her valedictory speech six months prior to the catastrophic EU referendum, having reaffirmed her passionate commitment to the European Union, Shirley Williams presciently said this:

“We have to contribute to the huge issues that confront us, from climate change through to whether we’ll be able to deal with those multinational companies wishing to take advantage of us.”

In a period of, as she put it ‘great tension, strain and fragmentation’, Shirley placed an especial emphasis on the linkage between the climate crises and the issue of refugees coming from amongst the most disadvantaged people in the world.

In my judgement some of us, and certainly our children will live to see the collision of those two realities – the repercussions of climate related disasters will vividly reappear in the form of multitudes (and I don’t believe that will prove to be too strong a word) ‘multitudes’ of refugees seeking salvation wherever they can find it.

Throughout her career, as a committed internationalist Shirley had great faith in UN institutions such as UNHCR.

As a proud past-President of UNICEF UK, I only wish I could believe either agency had the resources, along with the required political support to match the scale of the climate driven crisis I see as inevitable.

The failure of an agreed international response can only lead to each nation developing its own answers – fertile ground, if it were needed, for renewed authoritarian rules – but it’s doubtful they’ll be called ‘Enabling Acts’ – that brand’s already been tarnished!

So, this is where I return to those early conversations with Albert Speer, who all too late came to understand that the most troubling fault line in human behaviour is the fatal link between ‘Power and Fear’, each feeding the other to create a toxic and combustible brew. One that perfectly serves the policies and purposes of corrupt autocracies, one that can only be faced down by a committed and unflinching adherence to plural Democracy.

Mirroring the anxieties of many of those angry Brexiteers in 2016, I feel I’ve had my country of birth, and the values I believed it to represent, stolen from me.

It’s worse than that, I find myself embarrassed by what, on an almost daily basis I see it becoming – my old enemy Rupert Murdoch’s dream made real. He never liked Britain, and he’s kind of won, he’s helped remake it in his own malevolent image.

It doesn’t have to be that way – politics is important, public service continues to attract utterly decent people knowing that Governments come and go.

I once heard Douglas Hurd, a man for whom I had great respect, say words to this effect:

“The duty of Government is to steer the ship of State through waters that are inevitably rough, sometimes even treacherous, and bring it back into a safe harbour for another group of honest men and women to assume the same responsibility.”

That perfectly conveys my idea of the process of Government which has, and can in the future, be carried out responsibly and well.

At present I don’t believe that to be the case.

Which is why I’m leaving the House of Lords with a pretty heavy heart; in the years that are left to me I’ll do what I can to support and celebrate the achievements of the next generation of progressive politicians, whilst offering every form of encouragement to my own wonderful West Cork community, as they face the headwinds of what I’m certain is going to be a very difficult future.

My recent experience suggests that it’s here in small communities that the concept of trust remains valued and reciprocated – maybe it’s here that the ‘resurrection’ our Select Committee report referred to can begin to have an impact; and who knows the powerful and inter-dependent worlds of politics and the media might begin to sit up and take notice?

I’m certain Shirley would approve of that!

Throughout my career I’ve tried to perform the role of an active (sometimes cockeyed!) optimist, so let me end on an encouraging note.

I’ve already mentioned that I live in West Cork on the River Ilen – a few hundred yards downstream from the Skibbereen Rowing Club.

When we first arrived thirty years ago the club was beginning to grow a local reputation, and a young Coach emerged from among its members named Dominic Casey.

Under Dominic’s tutelage this tiny club grew a regional, national, and eventually European wide reputation.

Five years ago it exploded onto international consciousness when two of its young members won a silver medal in the light-weight double sculls in Rio.

The post-race interview the two lads gave went ‘viral’ – a whole slew of local youngsters watched it and membership of the club soared.

This year in Tokyo, young men from the club came home with gold medals and women with bronze.

This success has given an unimaginable boost to the moral of our community, a sense of pride and achievement that money can’t buy.

This autumn my wife and I have watched at least two dozen crews and single scullers, in all weathers, training for the next Olympics – fully in belief of what’s possible.

It can happen, and thanks to people like my neighbour Dominic Casey I’m watching it happen – every day.

So the fat lady has yet to sing!

Thank you very much for listening to me.

David Puttnam, 15th October 2021, (4,789 words – 35 minutes)

Response to climate crisis must include the less-well-off, says President

Source: The Irish Times, 20/08/2021

President Michael D Higgins has called for a widespread societal response to climate change.

“Our planet is on fire and it will require a global and whole-of-society response. One of the good things is that there are very few climate change deniers now. They have headed for the hills,” he said at a cultural event in Co Carlow on Friday evening.

He reiterated that those who had contributed the least to the climate crisis were paying the harshest and most immediate price.

“We will be obliged to widen our perspective of home to all people on Earth in an act of international solidarity which will mean there will be some sacrifices we must make,” he said, noting that about 82 million people were displaced.

However, he questioned whether public figures had “the generosity of spirit or political intelligence” to deal with climate refugees and “absorb new groups of people”.

“What will be required is a merging of consciousnesses – the consciousness of the younger generation fighting on ecological matters and those who have fought for equality and justice,” he said.

Speaking to Lord David Puttnam on the topic of Ireland, Europe and the Climate Crisis at one of the opening sessions of the Festival of Writing and Ideas in Borris, Co Carlow, the President made reference to Irish research that has shown many of those suffering from bad housing and unemployment show the least interest in climate change. “It’s the well-off people who are showing the most interest in climate change but an all-of-society response will be needed so that communities can generate strategies and measures within their own communities.”

President Higgins said that on an international level there was a need for a “moral and intellectual awakening” and co-operation beyond national borders. He said that while he was pro-European, the European Union needed to pay more attention to different cultures. “The future of Europe can’t be reduced to a Franco-German conversation,” he said.

Speaking about Europe’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, he argued that Europe had lost the trust of countries in the developing world who were struggling to vaccinate their populations. “We’ve lost credibility in terms of global vaccination because we’ve been unable to find a mechanism to deal with intellectual property to allow other countries to produce vaccines as they need them. This won’t be the only pandemic we will experience, so we have to be willing to make changes.”

He made specific reference to the power of lobbyists with vested interests stopping good action on climate change and the distribution of pharmaceuticals. “There are 35,000 lobbyists in the European Union and 12,000 in Washington DC. It’s a cop-out to say that we are all guilty of vaccines not being delivered to Africa. It’s an exercise of power.”

Responding to a question from the audience on what farmers can do in terms of climate action, President Higgins said, “It’s a question of getting out of the American-style farming that was introduced into Europe. Farmers need an assured income … We’ll have to privilege different forms of production. If you consider that we import 55 per cent of our food yet we are one of the biggest producers of infant formula in the world.”

In one of his concluding remarks to a masked audience of about 200 people, he said, “There has been great empathy shown during Covid which if available, could get us to a new place.”

The Borris Festival of Writing and Ideas in Borris, Co Carlow, continues until Sunday. festivalofwritingandideas.com

Source: Times Higher Education

The first thing that strikes me in reading Sir Michael Barber’s new report into digital teaching and learning during the Covid-19 pandemic is how incredibly encouraging it will be to practitioners.

The publication of Barber’s report – by the body he chairs, England’s Office for Students – comes at a time when higher education institutions the world over are scrambling to adapt their pedagogical models to the online environment.

One of the report’s most resounding messages is that simple “adaptation” won’t cut it. If we are serious about taking advantage of technology that will allow digital learning to thrive, we must be far more imaginative, we must invent something new – something that embraces all the possibilities the digital sphere has to offer. If we get this right, digital delivery can enhance learning rather than acting as an inconvenient stopgap as we itch to get back to the classroom or lecture hall.

Papering face-to-face lesson plans onto a digital format cannot possibly be the answer.

For the past 10 years, I have been teaching film, leadership and creativity to students online, at universities everywhere from Australia via Singapore to Sunderland. Despite everything I thought I’d learned as chancellor of the Open University, I discovered that digital learning was still seen as a poor relation to the “real thing”, and that few in higher education seriously contemplated incorporating it into their daily practice.

My approach to digital teaching in those early years involved a lot of trial and error – it was no surprise to find that small groups worked better than large ones. More surprising was that levels of engagement could, if anything, be enhanced. I also discovered that I could only be as effective as the course leader I was working with – we had to function as a team.

Over the past decade, one of the most rewarding aspects of teaching online has been the sheer diversity of students with whom I have been lucky enough to engage. Thanks to my ever-evolving Cisco Webex connectivity, I can sit in rural West Cork and share film clips, music tracks and archival footage with students in Brisbane, Munich and Belfast, debating, discussing and exchanging ideas in real time.

In his introduction to the report, Sir Michael talks about the “warm enthusiasm” he encountered from across the sector as he conducted his review. Indeed, students and teachers have often described the online model as feeling more personal and more accessible, especially when compared to sitting in (or standing in front of) a vast lecture hall.

The potential for greatly improved access to leading scholars and practitioners anywhere in the world is certainly something to be enthusiastic about. I invite “guests” into my seminars, and all that’s required of them is a laptop, decent connectivity and an hour of their time. No complicated scheduling, no air fares and soulless hotel rooms – in fact, far greater convenience and flexibility at appreciably less cost. Most important of all, the students love coming face to face with the heroes and heroines of their own particular discipline.

But the evident enthusiasm of Sir Michael and his colleagues can only get us so far. What is special about this report is the blueprint it provides for best practice. Its recommendations for immediate action (on page 15) provide something of a how-to guide for universities thinking about significant and possibly overdue improvements to their digital offering.

It is vital that practitioners be encouraged to develop the skills and confidence they need to move seamlessly between the online and offline worlds. It’s equally vital that students have a seriously influential voice in the strategic planning that goes into the next generation of teaching and learning practice.

Of course, beyond that, interdisciplinary and inter-institutional conversations need to take place to ensure that best practice results in a rising tide that lifts all boats. As I have learned from many years in the film industry, sharing creative ideas is always the best way to keep a sector innovative and alive.

For me, a constantly inspiring example worth following is the development, over this past decade, of the New York Times. In its use of embedded video, long reads and brilliant graphics, it represents a daily case study of the type of evolution I believe the digital world can bring to delivery of higher education. What matters most is that, in a post-truth world, at no time have these changes ever been allowed to compromise the paper’s journalistic standards.

I’m convinced that we in education can do the same.

The following piece appeared in The Irish Times on Saturday, January 2, 2021:

It was a year few will wish to remember and many will wish to forget. Historians will analyse 2020 long into the future and inevitably offer judgements on how well the crisis was managed.

For many of its future chroniclers, 2020 will actually be seen as a pivotal moment that provided the fuel needed to accelerate a number of changes that were already taking shape. This is particularly true in relation to our habitation of the digital world; over the past nine months, more than ever, digital devices have provided entertainment playgrounds, shopping centres, newsstands, political battlegrounds and windows to the outside for vast populations across the world.

These online spaces have given us a much-needed sense of connection during the grimmest days of lockdown, but how much have we really thought about their seamless integration into our daily lives? If we’re not careful, there is a danger that the aftershocks of our migration online will eventually eclipse the great earthquake that has been Covid-19.

Since the first case of the virus was diagnosed, we have seen a proliferation of untruths spread online about its origins, about supposed remedies for its eradication – some promoted by the US president himself – and now we face a similar barrage of ‘fake news’ in relation to the alleged dangers of vaccination.

From this point of view, a contagion probably more lasting than the coronavirus is rapidly spreading across our world; we are in the midst of a pandemic of misinformation and disinformation and we desperately need to do something about it. If we don’t, and counterfeit truths are allowed to flourish, there will be an inevitable collapse of public trust. Without trust, democracy as we know it will simply decline into irrelevance.

From June 2019 to June 2020, I chaired a House of Lords Select Committee that looked at this very subject; the impact of digital technologies on democracy. Over the course of the evidentiary hearings, our all-party committee came to the conclusion that online platforms are distorting our belief in what we see, hear and read. We have arrived at a situation in which we no longer know who or what to trust.

Indeed, this sense of collective mistrust has filtered into the public discourse beyond the walls of our digital devices, to be seized upon by some politicians in the real world as a form of political weaponry. Recent plans by the UK government to renege on the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement and break international law seem to have employed a lack of trust as a negotiating tactic.

These same politicians have also often used social media platforms to communicate with voters in digital walled gardens, unchecked by the free press or held to account by the opposition.

During my time as chair of that select committee, it became clear that social media companies have the ability to be far more responsible with the amplification of information online, but wilfully refuse to change the way in which their algorithms work because it would be detrimental to their business models.

This is not the first time big business has been resistant to change in the face of evidence that their products are causing harm to their customers.

In the late 1950s, when consumer-advocate Ralph Nader challenged General Motors to take passenger safety more seriously, having first made grotesque attempts to undermine his credibility, the company refused to take action because it thought safety devices would be bad for business. Consequently, security features (like basic seatbelts) in the cars we drive today are there in spite of the largest automobile companies, not because of them.

The early 1990s saw a similar pushback from the tobacco industry when it was challenged about the harmful effects of nicotine – despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary each of the big tobacco companies consistently denied their products were addictive, fraudulently protecting their business interests over those of their consumers.

‘Big Tech’ now faces its own day of reckoning. In recent weeks sweeping new powers have been proposed in Ireland, the UK and the EU for online safety legislation.

In the UK, the long-awaited Online Harms Bill outlines a “legal duty of care” for companies to remove content considered “harmful”. However, the definition of what that ‘harm’ encompasses has been left frustratingly vague and, disappointingly, disinformation and misinformation have so far been omitted. It’s obvious they must be included in any legislation that is serious about harm to citizens.

On 9 December, the Irish Government published its own Online Safety Bill that is similarly narrow in its definition of ‘harms’. However, it will establish a new media commission which may propose a more inclusive definition of “harmful online content”.

In Brussels, in conjunction with a new Digital Markets Act to tackle unfair competition, a Digital Services Act was published on December 16th. It proposes requirements for tech companies to take greater responsibility for illegal behaviour on their platforms.

From Ireland’s point of view, there is a long way to go before the proposals of the EU’s Digital Services Act are signed into law, and questions about whether the rules will be controlled at a national or a federal level remain.

It is proposed that a digital services coordinator be established in each state, but in the case of persistent infringements, the commission could intervene on its own initiative.

As the home to many of ‘Big Tech’s’ European headquarters, Ireland stands in a unique position in Europe. Balancing the economic and employment needs of its citizens with the need to legislate for a trustworthy and civil digital ecosystem will be a challenge for Ireland’s leaders in the years to come.

As with cars and cigarettes, a heavy price will be paid for failing to adequately regulate companies who place their business interests above the safety of citizens, let alone the security of the democracies in which we are lucky enough to live. We must not allow future generations to be the ones to pay that price.