The new Lords Democracy & Digital Technology Committee will seek to answer the crucial questions such as how our representative democracy can be supported, rather than undermined, in a digital world, writes Lord Puttnam.

Source: House Magazine

Social networks have brought many benefits. In the political sphere, they have enabled millions of people across the UK to engage in political discussion, sharing their opinions on issues of the day, and debating with others. But we’ve also found ourselves in a perilous situation whereby much of the political content tailored and served to each of us online is created, presented, and shared with few of the protections which have for many years, and with good reason, applied to print and broadcast media.

Serious concerns have emerged around the running and financing of our political campaigns. The corrosive effect of disinformation and manipulation has played a part in distorting both the facts and context of political discourse. The nature of public debate online can sometimes be vicious, abusive and all-too-often unacceptable. We need to consider whether this deters active participation, and what effect increasing levels of polarisation and radicalisation are having on our democracy.

Not all the answers to these questions can come from Parliament, although part of our response must be the development of far more effective forms of digital literacy.

The truth is few understand the algorithmic mechanisms of the tech giants, or how they enable the warping of our digital responses at a time when transparency could hardly be more important.

We need to look honestly and collaboratively at how best to address the magnitude of this challenge. Representative democracy is the cumulative effort of centuries, and it now falls to our collective stewardship to ensure that in seeking improvements, it is treated with all the care and attention it deserves.

We must at the same time recognise the immense benefits of the digital world.

For many people, digital technologies of all kinds have provided a means to more fully engage with the political process: to feel in closer contact with their representatives and the causes with which they most closely identify. Through these technologies, Government and Parliament can become more accountable to those they represent, and when responsibly deployed they have the potential to contribute to a healthy, well-informed democratic culture.

Facebook would appear to have acknowledged some of those responsibilities and signalled a desire to engage more formally with the political sphere, looking to lawmakers for a regulatory framework within which it might constructively channel its reformist impulses.

The task now falls to Parliament to engage with other social networks in a manner which effectively holds them to account for failings in their civic responsibilities whilst encouraging their potential to widen and enrich our democratic processes and interactions.

The crucial question we must both ask and answer is how representative democracy can be supported, rather than undermined, in a digital world.

The House of Lords Select Committee on Democracy and Digital Technologies has set out to address this challenge. Our call for evidence remains open until Friday 20th September, and I’d encourage anyone with a serious interest in the future of plural, representative democracy to enter a submission. Our inquiry can only be as good as the quality of the evidence we receive.

The support and expertise of parliamentarians will be essential if our committee is to set out a vision to the Government of the type of fair and inclusive democracy the UK deserves in the digital era.

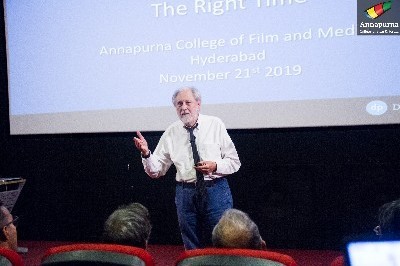

Lord Puttnam is a Labour peer and chair of the Lords Committee on Democracy and Digital Technology