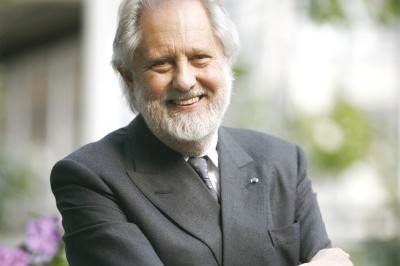

Puttnam: Elite kids as deprived as the poorest

Some behave like spoilt brats, but for the Labour peer and film producer David Puttnam, the children of some of the super-rich need help because they may be “as disadvantaged” as the very poorest in society.

“It’s a mistake to think that deprivation exists only with the very poorest in society: there are other forms of deprivation that go right through to the top,” Puttnam said.

He added: “Many people will find this a totally counter-intuitive ‘first world’ problem — but check with the principals of many of our most expensive schools and most desirable universities, and you will hear the same story: mental wellbeing is a significant and growing problem.”

His intervention in the debate about a phenomenon sometimes described as “affluenza” is significant because Puttnam is more usually concerned with tackling the problems of poverty.

He chairs the Cultural Learning Alliance, an umbrella group of 10,000 cultural organisations and leaders that launched a report last week on the value of art to empower underprivileged children. It said taking part in arts activities boosted children’s cognitive abilities by 17%, made young offenders 18% less likely to reoffend and made low- income children twice as likely to volunteer.

However, he told The Sunday Times that he was also keen to use the arts to help the offspring of the top 0.1%, who have an annual income of more than £600,000. “It is very difficult for people who have unlimited wealth to help their kids to lead moderated and engaged lives,” Puttnam said.

“There are any number of kids in London who I worry do not necessarily have directed lives. You have 18 to 22-year-olds whose idea of life is . . . the next party. People at the opposite end of the spectrum might think this is slightly barking: ‘How can it be? You are very wealthy — what do you mean you have a problem making sure your kids are engaged with the real world?’ But it’s true there is a real problem.”

The phenomenon has troubled Puttnam since the late 1970s, when he was producing Foxes, a film about four privileged California valley girls. The cast included Jodie Foster.

The script had one of them commit suicide, but this was changed to a car crash, Puttnam said, when real life overtook fiction in the form of a string of suicides among the offspring of movie stars. “That was the first time I was confronted with the reality that there were some very awkward facts relating to the children of privilege, which people of privilege did not really want to talk about,” he said.

Pictures of rich kids flaunting their lifestyles have become a social media phenomenon, but Puttnam suggests we look beyond the photographs shot in the cabins of their private jets to understand their antics. Their lack of empathy may spring from seeing little of their parents, he suggests, and being spoilt when they do see them.

One pioneer in the study of this field, Suniya Luthar, professor of psychology at Arizona State University, found that children of affluent parents who earned more than £100,000 had twice as much risk of developing mental problems as their poorer peers.

She pointed to the pressures on them as their childhoods were devoted to being groomed for success in a winner-takes-all economy. “The children of the affluent are becoming increasingly troubled, reckless and self- destructive,” she said.

Tanya Byron, a chartered clinical psychologist and professor in the public understanding of science at Edge Hill University, said: “Sometimes I meet these kids in their teenage years and they remind me of burnt-out executives in their fifties. They are so overwhelmed and stressed by the expectation — the pressure to hit these markers of success.”

Written by Nicholas Hellen